Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Book Review

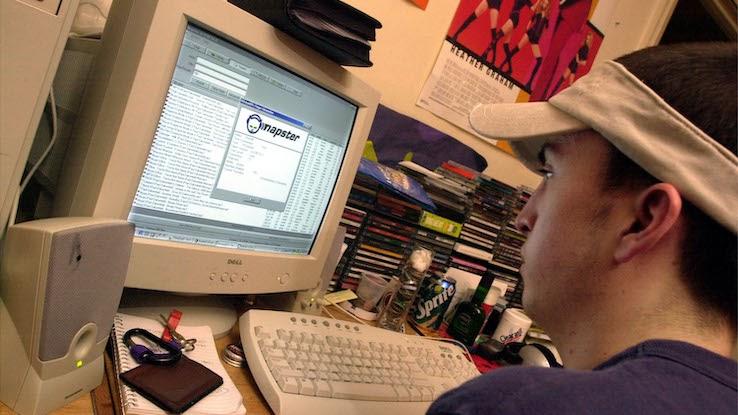

As you read this, there's a adept chance you're enjoying some amazing tunes through an online streaming service like Spotify, Pandora or Apple Music. Or maybe you prefer keeping things a little fleck old-school with your trusty iPod and — fix for it? — headphones that actually have wires. No matter what your favorite mode to tune in might be, it's safe to say the way nosotros listen to music, non to mention the music industry itself, has evolved drastically in the last couple of decades. Many people credit this musical revolution to the peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing software program Napster.

Simply Napster's appeal to everyday listeners — namely the power to expand their music libraries without having to pay to access that new music — was also responsible for its downfall. After facing costly lawsuits from irate executives and artists, Napster shut downwardly its servers in July of 2001. Equally we approach the two-decade mark since Napster'south demise, nosotros're taking a look back at the rise and fall of ane of the near controversial web-based applications in internet history, from its origins to the mode information technology changed the music industry forever.

The Rise of Napster: What Led to the Digital Sound Formats of Today?

Before nosotros dive into exactly what Napster was, it helps to take a look at the different ways music storage was fabricated commercially available to us — and how these sound formats evolved. Starting in the 1800s, if people wanted to own music, they purchased large discs made from difficult safe or shellac that were stamped with grooves to create vibrations that played songs. These were some of the earliest records people had access to. In the 1940s, manufacturers started making the discs from polyvinyl chloride, giving ascent to the term "vinyl" in reference to record albums.

By the mid-1960s, electronics companies had figured out how to store music on magnetic tape spooled in plastic housings. Known as viii-track tapes, they enjoyed widespread employ before slimming down to smaller cassette tapes in the 1980s. And these analog methods of playing music became near-extinct when compact discs (CDs) invaded record stores everywhere. After dominating the market as the music-storage format of choice for several decades, however, CDs, besides, were eventually eclipsed. A new innovation was on the horizon — and we weren't going to demand physical storage methods like records, cassette tapes or CDs to access our favorite songs anymore.

When personal computers began to see more widespread use in the late 1980s and early 1990s, programmers developed methods of storing sound digitally to provide the audio on their software programs. Music industry executives likewise saw dollar signs in the determination to produce CD-ROMs that independent songs stored as digital Waveform Audio Files (WAV) on these discs. As with whatever technological advocacy, users establish ways to copy WAV files from their CDs and shop those files on their computers. This meant someone could purchase an anthology on CD, copy the music to their estimator and shop it on the same device.

And this besides meant people could share that music with family unit and friends. Like copying a cassette tape, the premise of making copies of songs or creating playlists to give to our high school love interests wasn't exactly something new. Merely in the tardily 1990s, music sharing was set to go global when programmers Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker created an application to share digital vocal files amongst millions of users.

Napster essentially pioneered P2P file-sharing clients. But what exactly does that hateful? Users "ripped" WAV files from CDs, meaning they copied the digital sound files from CDs to programs on their computers and condensed that digital data into smaller files — what we at present know equally MP3s — that were more suitable for fast downloading. They then uploaded these MP3 files to Napster'southward service, saving the files with the music creative person'southward name and the song championship. Past downloading Napster, users essentially joined a network that gave them access to the file libraries of anybody else who was also using Napster.

A user could operate Napster's search function to look for a rails proper name or creative person, and the file names popped upward in search results. After a quick double-click and a few minutes, the file downloaded to the user's computer, where they could so transfer it to a portable media histrion like an iPod. The more people who downloaded the MP3, the faster the file downloaded — and the further information technology spread to new users without people having to purchase the actual albums the songs were officially available on.

Once someone had downloaded music files for complimentary, they were able to do what they wanted with those files — technically speaking, merely maybe not ethically then. And record labels and artists weren't able to contain this widespread, illicit distribution of music, so they weren't able to profit from it the style they expected to. Thus began the dorsum-and-forth battle between record labels, artists and consumers on the ethics and legality of P2P file sharing.

Napster Fell Just as Apace as It Rose

At its peak, Napster had about 80 million registered users — a surprising number considering that the service was simply operational from June 1999 to July 2001. And this massive popularity besides apace raised the ire of music industry professionals who were concerned about the loss of profits and uncontrolled distribution of their intellectual property.

In 2000, Metallica sued Napster and a few colleges, including USC, Yale and Indiana University, for encouraging students to re-create songs. Drummer Lars Ulrich wasn't shy with his criticisms of the service, saying, "Information technology is sickening to know that our fine art is existence traded like a commodity rather than the fine art that it is." Even after facing fierce backlash from fans who thought the determination was purely financial, Ulrich'south stance didn't waver. In a 2014 Reddit AMA, he wrote, "The whole thing was virtually ane thing and i thing but — control… If I wanna requite my s*** away for free, I'll give it abroad for gratis. That choice was taken away from me." Ulrich also appeared before Congress, accusing Napster of copyright infringement and testifying near its potential damages.

Dr. Dre, hip-hop pioneer and founder of Death Row Records, lost coin as both an artist and a producer due to file-sharing on Napster. He filed a lawsuit in 2000 confronting Napster while leaving open up the possibility of suing individual users. In a statement, Dr. Dre'southward attorney Howard King was blunt: "If information technology turns out that there are people who take huge hard drives and actually are downloading copyrighted materials and transmitting [them] on the internet, nosotros may very well go subsequently them because they are engaged in theft."

Napster eventually reached settlements with diverse artists, tape labels and the Recording Industry Association of America and was ordered by a federal judge to cake music from whatever artist who didn't want it to be shared on the service. As a result of the litigation, Napster shut down its servers on July eleven, 2001, and tried to transform into a paid service that never defenseless on.

Not All Artists Protested the Service

Maybe surprisingly, some music artists have cited Napster as a catalyst for their popularity, not a detractor, because information technology allowed many more people to discover their music. The folk/stone band Of A Revolution (O.A.R) became a nationwide success on college campuses with the song "Crazy Game of Poker." The reason? "Napster led to what nosotros can do today," drummer Chris Culos told the Annoy Herald. "Once people constitute out about the band [via Napster], they went back and supported u.s.a. past buying records, coming to shows, or passing it on to their friends. In our case, Napster was huge."

Several artists were thrilled at the innovative method Napster presented for reaching much broader audiences. Chris Cornell of bands Soundgarden and Audioslave said, "I retrieve this aspect of technology is really going to bring a lot of different angles of life and commerciality out of the corporate world and give it back to the individuals." Co-ordinate to AV Order, Napster was also responsible for turning Radiohead into "global superstars." The English band had never had a top-20 hit in the U.S., simply afterwards their 2000 album Kid A made its way to Napster three months before its release date, millions of people began downloading it — and Kid Adebuted at the number-one spot on the Billboard 200 sales chart.

The value of Napster as a potential promotional tool became role of its entreatment in an increasingly divided industry. Even artists like David Bowie, Billy Corgan and Limp Bizkit happily adapted to the new method for sharing music across the globe. Napster represented an exciting new way for artists to reach fans, fifty-fifty if other established artists — and federal courts — didn't share the sentiment.

The Cease of an Era: Napster'south Rebirth and Adaptation Fizzle Out With Fans

Software visitor Roxio, which creates programs for burning CDs and DVDs, purchased Napster's brand and logos in a defalcation auction soon after the shutdown in an try to re-brand another music service information technology bought, Pressplay, as Napster 2.0 — a paid version. Napster then changed hands again following electronics giant Best Buy's purchase of the service before transferring once more to Rhapsody, 1 of the first streaming services to offer the monthly-subscription format that leaders similar Spotify and Apple Music now follow.

In Baronial 2020, Napster was again sold — this time to MelodyVR, a virtual reality concert platform. Throughout all these transformations and corporate transactions, users jumped transport, not knowing how the platform would change over again with each new sale or rebrand. Today, about three million people use Napster — a far fall from the 80 meg users the service saw at its new-millennium peak.

Although the music industry won the battle against Napster, the war to finish free digital music sharing continues. BitTorrent, a like P2P sharing platform, is now the nigh common method for sharing music, movies, books, calculator software and other digital files. More 170 million users are active on this platform, despite internet service providers' frequent attempted crackdowns on users who pause copyright infringement laws.

Today, many artists produce their music on dwelling studio computers, host self-booked tours and promote themselves on social media, funding success without the backing of big record labels. Napster's democratization of music potentially sparked the movement that freed artists to go contained of record labels in ways they couldn't accept anticipated xxx years ago.

Other aspects of Napster may take been far ahead of their time, as well. Remember those pesky digital files that led to Napster's downfall? Many of today's artists include free downloads of their albums with a vinyl record buy, eliminating the need to download songs illegally to obtain digital copies. As The Groovy Pumpkins' Billy Corgan stated early on, "This revolution has already taken place" — but the music manufacture is undergoing continual revolutions even today. And Napster deserves credit for taking the risks that ultimately spurred this digital revolution.

Source: https://www.ask.com/entertainment/napster-20-years-later?utm_content=params%3Ao%3D740004%26ad%3DdirN%26qo%3DserpIndex